In the high-stakes game of geopolitics, the United States finds its strategic gaze once again diverted away from the Asia-Pacific by wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, raising questions about the resilience of its alliances and the future of its influence in a region shadowed by China’s ambitions.

The US inevitably being distracted from the region is not a concern to which Secretary of State Antony Blinken would concede. Earlier this month, he told reporters that Washington will maintain an “intense” focus on the Asia-Pacific despite global conflicts elsewhere.

But history shows such promises are likely to go unfulfilled, according to Anu Anwar, a non-resident associate at Harvard University’s Fairbank Centre for Chinese Studies.

“One of the ironies of contemporary US foreign policy”, Anwar said, is that the last three administrations “all sought to laser focus on the Indo-Pacific region”.

“Yet, they all got distracted by events in other parts of the world,” he said, noting that if the Gaza conflict spreads and the war in Ukraine further escalates, “the US will undoubtedly have to divert its resources that would otherwise be allocated to the Indo-Pacific region.”

One need only go back to 2011 to find comparable circumstances. Then, in a bid to counter China’s growing influence, President Barack Obama’s administration announced that the US would “pivot” to Asia by rebalancing its resources and priorities towards the world’s most populous continent.

But not long after, Washington found itself entangled in the fight against global terrorist groups ranging from al-Qaeda to Islamic State, along with a civil war in Syria, on top of its then-ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and its efforts at brokering a nuclear deal with Iran.

The pivot to Asia – aimed at strengthening everything from cooperation on climate change to regional security, trade and investment – unsurprisingly, found itself sidelined.

In 2017, at the start of Donald Trump’s administration, Washington sought to reassure its allies and partners of its continued commitment to the region by rolling out the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” concept. This was to ensure “the global commons are accessible to all” and “disputes are resolved peacefully” by embracing fair and reciprocal trade, as outlined by former US secretaries of state Rex Tillerson and Mike Pompeo.

But just days into his presidency, Trump pulled the US out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a comprehensive regional trade deal aimed at limiting China’s economic outreach.

The US once again pivoted back to the region following the election in 2020 of current President Joe Biden, who has hosted White House gatherings with leaders of Pacific nations and of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

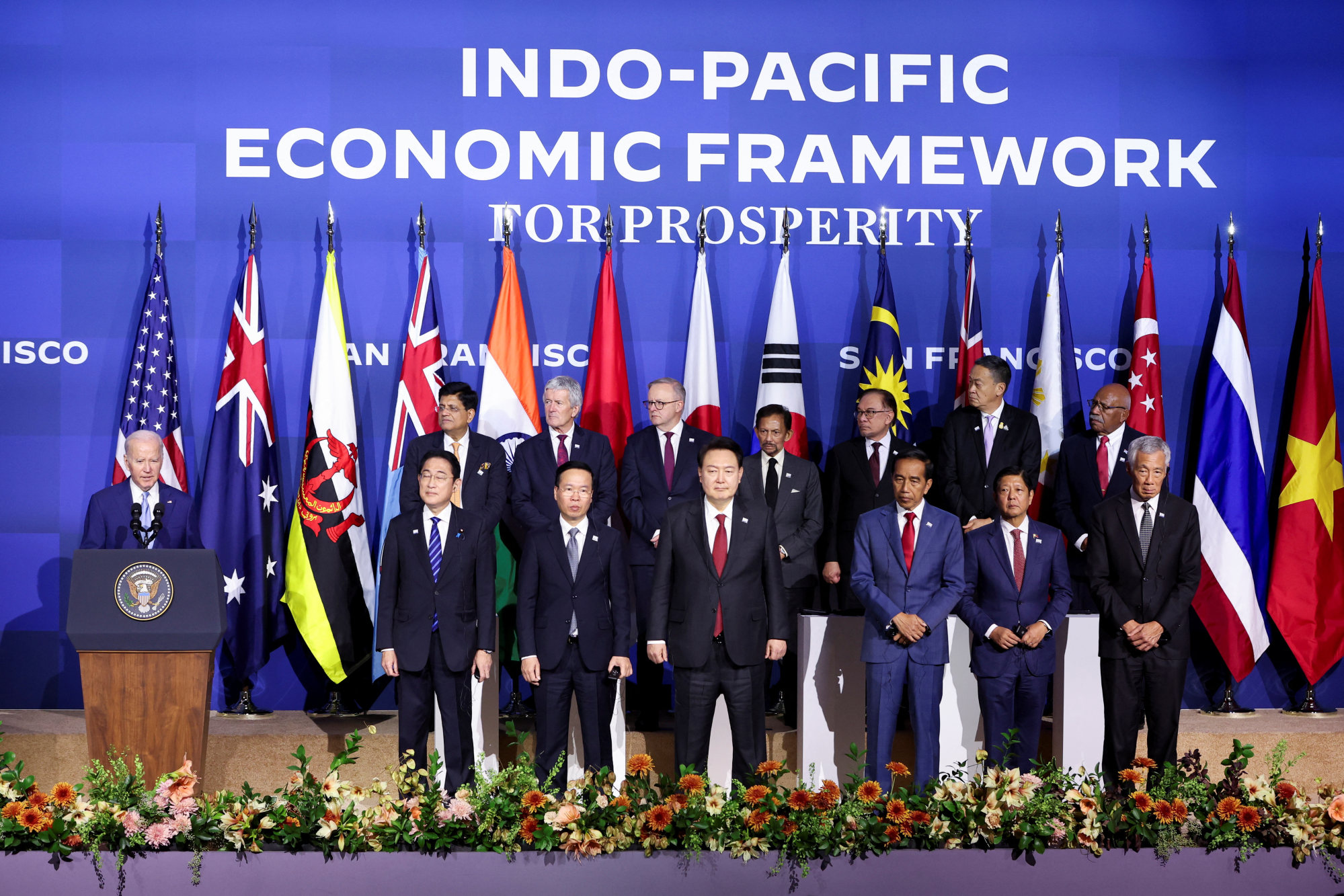

Apart from agreeing to sell nuclear submarines to Australia, Biden’s administration also came up with the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) as a replacement for the abandoned TPP.

But with a US presidential election looming next year, as well as ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, most analysts expect Washington’s attention to once again move away from its pivot.

The difference this time may lie in the strength of alliances that the US has forged with regional partners. When Blinken claimed on November 8 that the US could maintain focus on the Indo-Pacific while simultaneously handling multiple security issues, he cited a network of allies that the Biden administration has called one of the country’s “greatest strategic assets”.

The era of absolute US primacy in Asia may be over, but the US remains capable of bringing significant capabilities to bear across multiple regions

Alice Nason, foreign policy and defence researcher

“The era of absolute US primacy in Asia may be over,” said Alice Nason, a foreign policy and defence research associate at the University of Sydney’s United States Studies Centre. “But the US remains capable of bringing significant capabilities to bear across multiple regions.”

The “empowerment” of allies has been “the overriding priority” of the US’ Asia strategy since Biden entered office, Nason said, adding that ongoing conflicts will slow down “rather than stall” the momentum of US defence and diplomatic partnerships in the region.

Relying on friends and allies

If Washington becomes overstretched, fewer resources spent on hemming in China’s activities would mean fewer “freedom of navigation operations” and reconnaissance sorties around the country’s periphery.

There would also be a slowdown in the forging of new alliances and the delivery of arms to Taiwan and other allies, Anwar said.

Concerns about China taking advantage of an overextended US military are the reason Washington has placed so much emphasis on fostering security-cooperation initiatives in the Indo-Pacific, according to Muhammad Faizal Bin Abdul Rahman, a research fellow on regional security at the Singapore-based S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

One example is the US military’s cooperation with the Philippines under the Enhanced Defence Cooperation Agreement (EDCA), which allows US forces to position and store defence materiel, equipment and supplies in the Southeast Asian nation.

Another is the information-sharing deal between the US, Japan, and South Korea, struck this month but planned to begin in December, on North Korea’s missile activities, he said.

In the South China Sea, Philippine and Chinese ships have become embroiled in increasingly frequent naval skirmishes, including two collisions near the disputed Second Thomas Shoal last month.

Tensions appeared to ease somewhat after Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr told Chinese leader Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the Apec summit on November 17 that disputes over the waterway should not define bilateral ties. Though back at home, Marcos has made it clear that the Philippines “will not give up a single square inch of our territory to any foreign power” and will continue to adhere to an international rules-based order.

To deal with the prospect of a crisis in the South China Sea, Stephen Nagy, professor of politics and international studies at the International Christian University in Tokyo, said “new mini-lateral relationships” will continue to emerge, especially between the Philippines, Japan and Australia.

Philippines races to upgrade its degrading military in the face of maritime disputes

The Philippines recently said it had approached neighbours Malaysia and Vietnam to discuss a separate code of conduct regarding the disputed waterway, citing limited progress towards striking a broader regional pact with China.

Optimistic that Washington has the capacity to “keep its eyes” on the region, Nagy said it was not just the US that provides a framework for stability but also its partnerships and alliances, forged through Washington’s long-standing military engagement with the region.

Japan and Australia, he said, have stepped up to create reciprocal access agreements – defence pacts between countries aimed at providing shared military training and operations – and provide infrastructure and connectivity aid to the region.

Earlier this month, Japan and the Philippines agreed to seal a reciprocal pact that would allow their troops to enter each other’s territory for joint military exercises.

We should be clear that the US does not do this alone

Stephen Nagy, international-studies professor

Japan and Australia also have a similar treaty to facilitate joint drills and strengthen security cooperation, which came into effect in August.

“[These pacts] ensure that the US understands that they are increasing their burden sharing within the partnerships,” Nagy said, noting that if crises occur both in the Taiwan Strait and on the Korean peninsula, Japan, Australia and New Zealand would be focused on the former while South Korean forces, backed up by the US, would deal with the latter.

“We should be clear that the US does not do this alone,” Nagy said.

University of Sydney’s Nason agreed that “the US relies on capable partners now more than ever to meet its regional security objectives”, adding that Washington’s sustained attention on its Indo-Pacific alliances and partnerships since the war in Ukraine began in February last year was a source of assurance.

“[It reflects] the Biden administration’s ability to ‘walk and chew gum’, attending to different regions simultaneously,” she said, noting that Washington has, for example, signed a defence pact with Papua New Guinea this year that will allow Port Moresby’s personnel to join US coastguard ships patrolling the region.

“Competing for influence in the Indo-Pacific has been elevated as a bipartisan priority in a Congress divided in almost every other area,” she added.

Part of that influence involves better arming its allies, Nason noted. Not only is the US helping Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines – the first of which are scheduled for delivery in the early 2030s – it has also announced four new EDCA sites in the Philippines.

Jacob Stokes, a senior fellow with the Centre for a New American Security think tank’s Indo-Pacific Security Programme who focuses on China, said Washington understood clearly that “China is not going away, far from it” and would thus not overcommit in another direction.

“While Washington staunchly supports both Ukraine and Israel, the US has not committed to fight directly on either’s behalf,” Stokes said. “That restraint stems in part from a recognition that US military power is needed in East Asia to deter aggression there.”

In addition to its growing aggression in the South China Sea, Beijing has also been carrying out military drills around Taiwan, including last Sunday, when nine of its aircraft crossed the median line in the Taiwan Strait, which serves as a de facto dividing line.

Beijing regards the island as a breakaway province to be brought under mainland control – by force, if necessary. Many countries, including the US, do not officially recognise Taiwan as an independent state but oppose the use of force to change the status quo.

A big gap to fill

Despite the dense network of US-aligned security partners around the Asia-Pacific, analysts say Washington’s diminished focus on the region will still have a big impact.

While Japan and, to a lesser extent, India are expected to step up their efforts in the region if Washington is distracted, Anwar described their roles as “supplemental” and “not a substitution for the US”.

“The US does all the heavy lifting,” he said, adding that no other country was in a position to fill the gap.

Kei Koga, an associate professor in the Public Policy and Global Affairs Programme at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, said that while Japan hopes to take on greater defence roles, it is limited both constitutionally and politically – though some of these constraints have been relaxed in recent years.

During and after former prime minister Shinzo Abe’s final tenure from 2012 to 2020, Japan increased its defence spending, expanded its alliance with the US, and reinterpreted its pacifist constitution in a way that would allow its troops to come to the aid of an ally under attack.

However, large pockets of the Japanese public have expressed concerns about their country’s growing defence capabilities, with 80 per cent saying they were opposed to tax increases aimed at financing defence spending in a poll conducted in May by Kyodo News.

“Japan’s role will be uncertain,” Koga said, noting that Tokyo could however coordinate its policies with other allies such as Canberra and Seoul as these would contribute to the “preparation for regional contingencies”.

A long Israel-Gaza war could become a “geopolitical quagmire” for the US, RSIS’ Muhammad Faizal said, explaining that it would create doubts about whether the US and the West’s advocacy for international law and human rights were “principled or self-serving”.

“It creates diplomatic and propaganda opportunities for China and Russia,” Muhammad Faizal added, noting that Washington would find it tougher to convince the region of its Indo-Pacific strategy while sustaining its support for Ukraine.

As for Israel’s siege of Gaza, many critics have accused Western governments of failing in their responsibility to act in the face of credible accounts of war crimes being committed.

They have charged that calls for a ‘humanitarian pause’ are a distraction and an abrogation of humanitarian responsibilities, and say a ceasefire is the only way to stop the bloodshed.

Already – through the use of visceral, emotional, politically slanted and often false narratives – Moscow and Beijing are using their state and social media platforms to disparage Washington and undercut Israel.

Case in point: a Russian overseas news outlet, Sputnik India, quoted a military expert as saying, without evidence, that Washington had provided Israel with the rockets that hit the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza on October 17.

The US’ staunch support for Israel is said to be driving a wedge between Washington and the Muslim-majority countries of Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia and Malaysia where resentment against the US is rife.

Poor economic engagement

US attempts at realigning Asia-Pacific partners away from China are made more difficult by Washington’s lack of economic engagement with the region, analysts say – a state of affairs that is unlikely to change given the ongoing wars, and which stands in stark contrast to Beijing’s enthusiastic investments.

The collapse of the TPP under Trump came as a disappointment to the region and its replacement, Biden’s IPEF, does not promise the sort of trade deals and lowered tariffs that many countries were hoping for. Instead, the US says the IPEF will advance “resilience, sustainability, inclusiveness, economic growth, fairness, and competitiveness”.

Nagy said the framework was not the sort of deal that allows the US to “anchor itself into the region through concrete trade initiatives”.

Indeed, while this month’s negotiations on the IPEF led to agreements on subjects such as clean energy and anti-corruption, the section on trade remains in limbo after no deal was reached.

Even without the ongoing conflicts, Harvard University’s Anwar said Washington’s economic commitment to the Asia-Pacific via the IPEF was already “under serious question” since the deal was “incompatible” with China’s multitrillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, as well as the volumes of trade and investment it does with the region.

“Now that these two wars have drained a large chunk of US economic resources, it will mean less investment in the region,” Anwar said.

Last year, total annual Chinese investment in belt and road infrastructure projects stood at US$67.8 billion, 34 per cent of which went to Asian countries, according to Statista, a German data-gathering platform.

In Southeast Asia, China disbursed about US$5 billion annually in development finance between 2015 and 2021, with infrastructure accounting for 75 per cent including projects in transport and storage, energy, communications, and water and sanitation.

By contrast, the US in 2018 announced a US$113 million Asian investment programme in new technology, energy and infrastructure initiatives in emerging Asia. This year, the US International Development Finance Corporation announced at least US$570 million in new financing for private-sector investments across Southeast Asia aimed at spurring economic growth, advancing financial inclusion, leveraging technology to expand access to education and healthcare, and supporting food and energy security.

Given the “stilted” progress of the IPEF from the outset, Nason said the US would continue “to walk on one leg in its Indo-Pacific Strategy” as it was militarily strong, but economically weak.

As for the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor announced in September, which is aimed at stimulating economic development through greater connectivity and economic integration across continents, Nagy said it would be unaffected.

“It has just been announced, it will take years for it to move forward,” he said, referring to the deal signed by the governments of the US, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, France, Germany, Italy and the European Union.

Under the vision, a railway is expected to link ports connecting Europe, the Middle East and Asia, while facilitating the development and export of clean energy and strengthening food security and supply chains.

Anwar predicted that progress on the project would be made more difficult by India’s deepening ties with Israel and its pro-Israel stance amid the ongoing conflict.

“[These] may put Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries on a pause as to how much deeper engagement they sought to build with India,” he said.

India’s formerly pro-Palestinian position has weakened during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s nine-year rule. His Bharatiya Janata Party, which is reliant on support from the majority Hindu population, has been accused of anti-Muslim hate.

Since the start of the war in Gaza, Modi has thrown his support behind Israel, with India abstaining from voting on a UN resolution calling for a ceasefire.

Source : SCMP